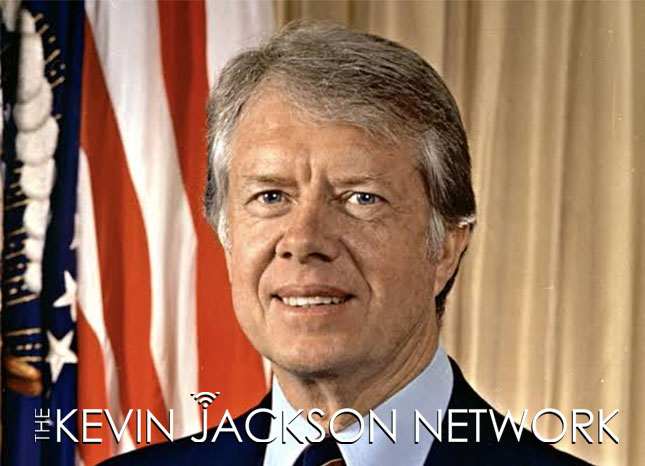

Jimmy Carter was one of the worst presidents in American history. But he wants to be remembered for building a few houses for poor people.

I get it. In death, we try to forget all the damage a person does, because certainly everybody has been redeemed. I remember a funeral I attended for one of my family members who was a straight-up thug. The pastor had nothing good to say about him, so he talked in generalities. But we’ve definitely got a case of selective scrutiny on our hands, as Carter’s racist past is being completely glazed over as if it never happened.

Often celebrated as a humanitarian and moral statesman, has a far more complicated past when it comes to race relations than many would care to admit. In his younger years, Carter worked hard to keep Georgia segregated, aligning with the racial attitudes prevalent among white Southern Democrats of the time. Like many in his party, when the political tide shifted, so did Carter’s stance—conveniently around the time he needed Black votes to climb the political ladder.

While Carter supported segregation, PBS is quick to point out that Carter once played with some black kids on the block during some intense race relations. As we said back in the day, “whoop-tee-do Mr. President”, that’s not exactly a fix for his racist demeanor. Yet, he was called, and I quote, a “God-damned ni**er lover.”

‘The Root’ described some of Carter’s early contradictions:

“To call Carter’s early relationship with the Black community complicated, would be the understatement of the century. As a candidate for Georgia governor, Carter cozied up with avowed segregationists, earning himself a rather unflattering description from the premier state newspaper, the Atlanta Journal Constitution. In their opposition to his candidacy they called him “ignorant, racist, backward, ultra-conservative, red-necked South Georgia peanut farmer.”

But in his personal life, the rural Georgian politician had taken stances in favor of integration. At his Baptist church, Carter and his wife, the late Rosalynn Carter, were two of only three congregants to vote in favor of integration. (He later joined an integrated church, the Maranatha Baptist Church.) And as renewed segregationist sentiment swept through the South after Brown v. Board, Carter was one of the only white men in his community to refuse to join the local chapter of the white supremacist group, The White Citizens’ Council.

The clear contradictions didn’t go unnoticed by Black Americans, who overwhelmingly supported Carter’s primary opponent in the Georgia Governor’s race. But as evidenced by Black voters later support of Carter, his story doesn’t end there.

It’s hard to know exactly what changed with Carter. It’s possible that the fact he was no longer running in the Deep South meant he felt safe standing by the convictions he’d espoused in his personal life. But in his inaugural address as Governor in 1970, Carter hit a different note than his campaign, swearing “the time for racial discrimination is over.”

[END]

The truth is, Carter was a racist throughout much of his early life. His political transformation didn’t stem from personal revelation but from necessity. As his ambitions grew, Carter became a textbook example of political pandering—suddenly championing racial equality when it became advantageous to do so. Ultimately, Carter did evolve, proving that anyone is redeemable.

Now, imagine if Carter were a Republican.

Would he have received such an easy pass? Democrats and their allies in the media have a long history of excusing racist pasts within their ranks, while amplifying baseless accusations against Republicans. Take Donald Trump, for instance—never a proven to be racist, yet relentlessly attacked by the media and left-wing ideologues. The double standard is glaring, and it’s exhausting.

This isn’t just about Carter’s racial history. His record of appeasing America’s enemies has also been conveniently glossed over. As CNN’s Scott Jennings pointed out, Carter consistently sided with adversaries of the United States, further complicating his legacy.

It’s time for honest scrutiny across the political spectrum. Carter’s journey from segregationist to racial ally proves redemption is possible, but it also exposes the selective forgiveness reserved for Democrats. True accountability shouldn’t be partisan—it should be principled.